Yinka Olajubu

May 6, 2025

In many parts of the world, museums are revered as sacred spaces, not in the sense of religious sanctuaries, but as sanctuaries of memory, knowledge, and identity. They function as vital custodians of humanity’s collective experience, preserving artifacts, stories, and expressions that chart the rise and evolution of civilizations. These institutions are places where history, creativity, and innovation converge, offering the public a tangible connection to the past and a deeper understanding of the present. In cities across Europe, Asia, the Americas, and parts of Africa, museums are often central to national pride, integrated into education systems, tourism industries, and cultural policies. They are treated not merely as buildings but as living repositories of a people’s journey, reflecting values, worldviews, and accomplishments across generations.

In Nigeria, museums were founded with similar noble intentions. They were conceived as institutions to document and protect the country’s rich and diverse cultural heritage, showcasing the technological, spiritual, political, and artistic ingenuity of Nigeria’s many ethnic groups. These museums were meant to be more than just storage facilities for artifacts; they were envisioned as dynamic spaces for dialogue, learning, and identity formation, places where Nigerians could encounter their past, reflect on their present, and shape their future. They are meant to act as both archives and predictors: capturing ancient wisdom while inspiring contemporary innovation.

However, despite their foundational mission, Nigerian museums remain underutilized, underfunded, and often misunderstood. The institution of the museum has yet to be fully embraced by the very society it was built to serve. Rather than being seen as essential pillars of national identity and education, many museums in Nigeria are regarded with indifference, suspicion, or even fear. This disconnect reflects a broader cultural crisis, one where modern misconceptions, especially those rooted in religious or colonial biases, obscure the true purpose and value of heritage preservation. As a result, these institutions struggle to fulfill their transformative potential in shaping an informed, unified, and forward, looking society.

The Role of the NCMM: Preserving the Soul of a Nation

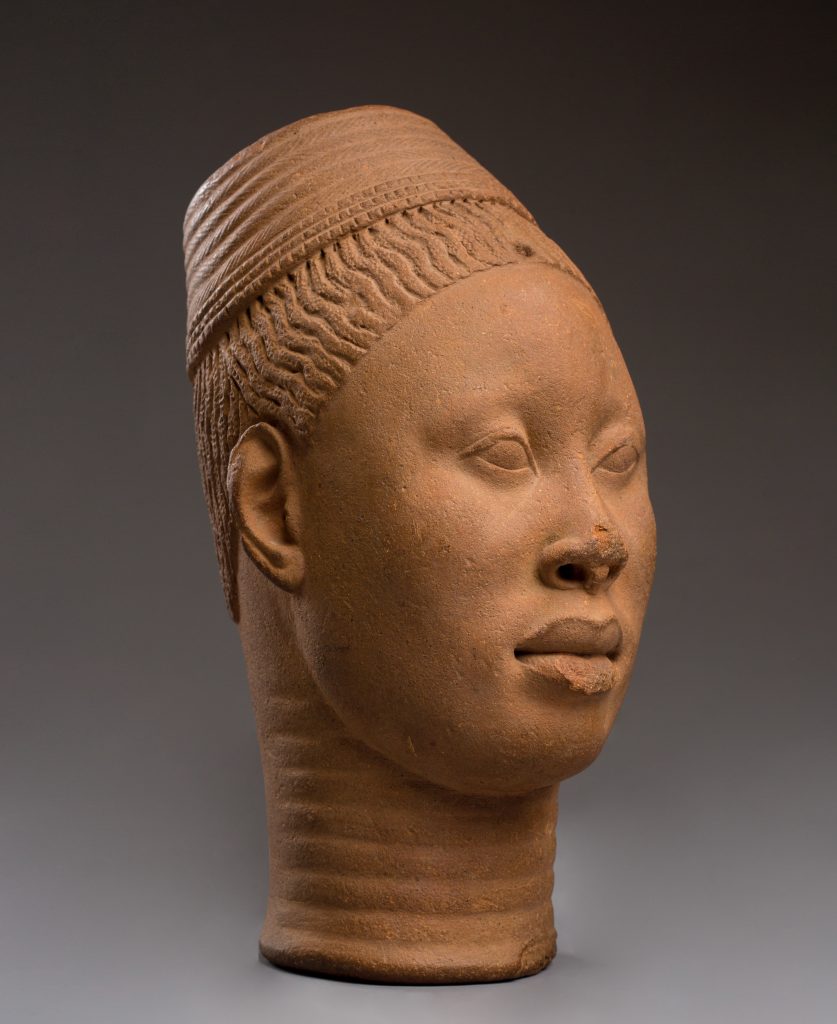

The National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) is the guardian of Nigeria’s collective memory. Through its widespread network of museums and heritage sites, it houses thousands of objects that stand as undeniable evidence of the civilizations that thrived across the diverse landscapes now known as Nigeria. These artifacts, elegantly sculptured terracotta figures from the Nok, intricately cast Benin Bronzes, woven Akwete textiles, ancient tools, ritual vessels, and ceremonial regalia, speak volumes of the sophistication, governance systems, aesthetics, and belief structures of our ancestors. They tell of a people who lived with meaning, organized themselves with intention, and expressed their values through masterful artistry and innovation.

These objects are not idols to be feared. They are not threats to religious purity or moral standing. Rather, they are material testimonies to the ingenuity, complexity, and creativity of our forebears. They remind us that long before colonial contact or the arrival of modern religions, there was civilization, rich, expressive, and ordered. The NCMM, in this regard, does not promote any deity; it promotes heritage. It preserves the human journey of Nigerians, one that deserves to be known, understood, and passed on.

Museums as Engines of Cultural and Economic Growth

Across the world, museums are thriving, not just as repositories of culture, but as dynamic engines of diplomacy, education, and economic development. In countries like France, the United Kingdom, China, and Egypt, museums are not passive institutions but active contributors to national development strategies. They attract millions of visitors annually, generate significant revenue through tourism, support thousands of jobs, and shape the global narrative of a country’s cultural identity.

Cultural tourism, especially, has emerged as a major contributor to GDPs in many nations. The Louvre in Paris, the British Museum in London, the Smithsonian in Washington, and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo are more than buildings, they are symbols of national prestige and tools of soft power. Scholars, artists, collectors, researchers, students, and tourists flock to these institutions not just for leisure, but for learning and inspiration. Their economic impact is undeniable; their social influence is enduring.

Nigeria, with its vast and diverse cultural heritage, holds similar potential, if not greater. From the Nok Terracottas to the Ife Bronzes, the Benin Kingdom masterpieces to Igbo-Ukwu treasures, we are home to world, class heritage. Yet, we have failed to properly harness this wealth. The Nigerian Museum system is riddled with neglect, poor funding, lack of infrastructure, and public indifference. Despite having the raw materials for a robust cultural industry, we have not transformed them into sustainable assets. Why? Because of a deep, seated misunderstanding that continues to undermine every attempt at progress.

Religious Misconceptions and the Crisis of Museum Identity in Nigeria

To say Nigerian museums have suffered is an understatement. For decades, they have been casualties of a profound identity crisis, caught between cultural preservation and religious suspicion. Despite their purpose being educational and historical, museums in Nigeria are frequently viewed through a lens of fear and spiritual unease. The collections they house, particularly those associated with precolonial spiritual practices, are often branded as fetish, demonic, or cursed.

This misinterpretation is fueled by religious ideologies, primarily from the two dominant faiths in Nigeria: Christianity and Islam. Both religions, in their most conservative expressions, preach a strong stance against idolatry and often discourage any engagement with ancestral objects. From pulpits and prayer houses to mosques and religious gatherings, congregants are warned against “unclean” or “pagan” artifacts. The museum, then, is unjustly labeled as a place of spiritual danger, a shrine to a past that must be rejected, rather than a portal to a past that must be understood.

This theological bias has done more than shape public opinion; it has influenced political will. Governments hesitate to invest in museum infrastructure for fear of backlash or appearing to promote traditional belief systems. Museum staff are sometimes stigmatized or ridiculed for their profession. Public outreach is stifled. Opportunities for international collaboration are underutilized. The result is a national heritage sector that is underappreciated, underfunded, and undervalued. But this need not be our permanent reality. A cultural reawakening is not only possible, it is urgent.

This misrepresentation was even embedded in the urban planning of Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city. When the Federal Capital Territory was being developed, land was thoughtfully allocated for national institutions that reflect the diversity and identity of the nation. At the heart of the city, adjacent to the National Mosque and the National Christian Centre (National Church), was a plot allocated for the National Museum. This placement should have been symbolic, a visual reminder of Nigeria’s three, fold identity: Islamic, Christian, and traditional heritage. Yet, instead of honoring this triad, the decision became controversial.

Some saw it as an attempt to equate the museum with the “traditional religion,” as if the institution’s purpose was religious rather than cultural. Over time, this perception led to political reluctance and bureaucratic paralysis. Successive governments, hesitant to invest in what was now framed as a shrine to “paganism,” allowed the allocated museum plot to be quietly taken over, without replacement, without public outcry. A national insult, quietly accepted.

But let us be clear: a museum is not a temple. It is not a site of worship. It is a place of knowledge, of memory, and of identity. It exists to tell the stories of a people, their struggles, triumphs, inventions, and transformations. When we reject our museums, we reject the story of who we are. And worse, we create a cultural amnesia that leaves future generations unanchored.

If Nigeria is to truly harness the power of its museums, we must first separate them from the fog of religious suspicion. This shift must start with education and public reorientation. Leaders of thought, educators, artists, and yes, religious leaders, must come to see that celebrating our cultural history is not in conflict with faith. In fact, understanding where we come from can deepen our sense of purpose and place.

There’s a sobering story that illustrates just how deep this misunderstanding of museums and cultural heritage runs in some parts of society. A museum professional once paid a visit to a place of worship, expecting a routine interaction. During the round of introductions, he mentioned that he worked at the national museum—an institution that should inspire national pride and cultural appreciation. However, what should have been a moment of recognition and respect quickly turned into an ordeal that laid bare the extent of misinformation and stigma surrounding museum work.

Rather than commending his role in preserving the nation’s history and cultural treasures, the preacher immediately cast suspicion on his profession. Seizing the moment, the preacher turned the museum worker into the central subject of his sermon. He warned the entire congregation of the so-called spiritual dangers posed by artifacts, ancestral objects, and museum collections. According to his interpretation, working with such objects meant engaging with demonic or unclean spirits. What followed was even more disturbing: the museum staff member was subjected to a rigorous “deliverance” session, prayed over and treated as though he were spiritually contaminated, simply because of his profession. He was not seen as a cultural ambassador or an educator, but rather as someone lost in darkness.

This experience is far from unique. Many museum professionals in Nigeria and beyond have similar stories, where their work is misunderstood, feared, or condemned—often by those with significant influence in their communities. These incidents highlight the urgent need for public education, interfaith dialogue, and cultural sensitization to bridge the gap between heritage professionals and the society they serve. Until the misconceptions surrounding museums are addressed, such harmful encounters will continue to undermine the value of cultural preservation and the dignity of those who dedicate their lives to it.

The Way Forward: Reclaiming Museums for All Nigerians

To undo the damage and reposition museums as vital cultural institutions, a collective effort is required. The federal and state governments must prioritize museum development as a strategic component of national identity and tourism. Funding, infrastructure, and legislation to protect museum properties and heritage should be non-negotiable. The National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) and its professionals must lead this transformation from within. They should actively engage in public education, community outreach, and partnerships with schools, religious institutions, and the media. Through exhibitions, mobile museums, and digital platforms, NCMM can demystify its collections and make them more accessible and relatable. Museum staff must also become cultural ambassadors—knowledgeable, visible, and proactive in changing perceptions and advocating for the value of heritage in modern Nigerian life.

Religious and educational institutions also have a critical role to play. Faith leaders must be encouraged to promote a more enlightened view of cultural heritage, clarifying that appreciating one’s history is not equivalent to idol worship. Interfaith dialogues and educational workshops can bridge this gap. At the same time, Nigerian history and cultural heritage should be embedded in the curriculum at all levels of education. Regular school visits to museums can help young people grow up seeing them as places of pride and learning, helping to dispel outdated stigmas.

The media and creative industries are equally powerful in reshaping public opinion. Artists, musicians, filmmakers, and journalists can tell stories that celebrate Nigeria’s diverse cultures and traditions. Well-crafted media campaigns can reposition the museum as a source of inspiration rather than fear. Ultimately, every Nigerian has a role to play—by visiting museums, asking questions, advocating for heritage protection, and rejecting unfounded stigmas, the public becomes an active force in preserving and valuing the nation’s rich cultural legacy.

Conclusion: Our Past, Our Power

In the end, what we choose to preserve says everything about who we are and what we value. The museum is not a place to fear, it is a place to remember, to learn, and to dream. If we continue to conflate culture with religion, we will not only lose our past but also cripple our future. The museum stands as a mirror to our collective identity. It is time we looked into it, not with suspicion, but with pride. Let us stop seeing our museums as altars to be avoided, and start seeing them as bridges that connect our rich history to a hopeful tomorrow

Leave a Reply